Traders and investors participation (dropout increase) in upcoming inflationary envrionment

- Jan

- Sep 20, 2022

- 19 min read

While this article will not go into details about how the upcoming tougher economic conditions might look like, or what specifically is the cause of them (as some of that has been pointed on past articles and will be so in future ones), the idea here is for the reader to take for granted that inflationary environment will lead to tougher conditions and potential decrease in market liquidity, opportunities and overall just more participants exiting the game rather than entering (on YoY basis).

It is expected from the reader to not extrapolate the current Q1/Q2 2022 environment as a guide for projections, since the real challenge of the inflation and supply chain issues is by no means yet seen and reflected in real economy or the markets liquidity. The consequences of this will be built within the next one-two upcoming years as there is delay effect due to how inflation spreads trough.

Keep one very important factor in mind when doing projections: While prints in CPI, supply chains disruptions, and all the geopolitical challenges across the globe are instantly impactful and displayed, their consequences are not yet fully absorbed within economic activity and dropout of productivity, mainly because the globalized economy of 21st century can absorb huge shocks on short term basis without showing the negative results quickly. This is why supply chain disruptions (initiated by lockdowns 2020) have been happening for nearly two years, but only now in Q2 is when the results on the backbone of the economy are starting to show everywhere.

The deflationary environment combined with an oversupply of items can absorb shocks short-term, which is why the wages, the factory outputs, and productivity have not yet suffered, but very likely are, once that initial absorbing buffers are eaten up and inventories start to shrink. Both on the resources side (supply chains), and output side (decreased factory output) and combined with overall high inflation rates (as we see currently in Germany for example).

Whatever projections made have to be kept with this in mind, the challenge is only yet to come, which will be reflected through decreased economic activity next year most likely, prolonged inflationary pressures with risk on markets being under constant pressure for two years if not more (equities, crypto, etc). In such an environment, traders and investors will be challenged much more, regarding how exactly will be outlined on the article below.

Now that we cleared this up, and we take for granted that we have probably seen the "rosiest" markets in 2021 that we will probably see for a while, let's see how a future harsher environment might challenge the trading and investing community.

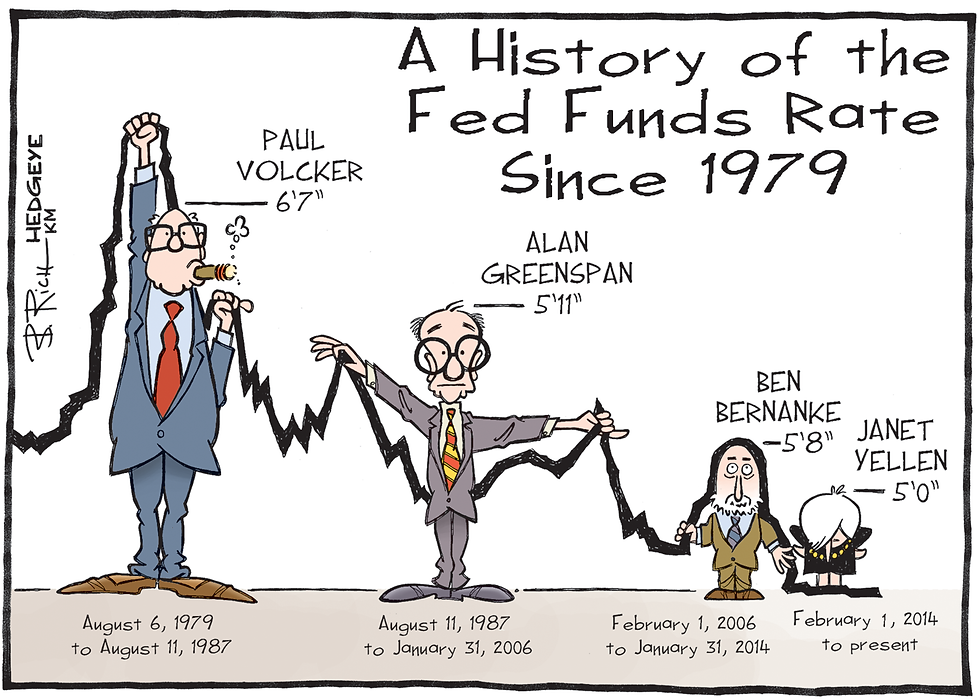

Easy money is gone, tight money enters the room

The 2020-21 cycle was perhaps the strongest easing monetary cycle we have seen on a global basis which explained why the markets were extremely good to trade or invest in and why so many had a blast over that period. The macro-environment of easy money (QE) combined with the "stay at home" combination of the situation created excess opportunities in markets. Typically the tops of bull markets skew the expectations of those entering markets fresh the most, and end with disappointment, often with a large chunk of those new arrivals leaving after the market tops and enters the bear phase. Such as we have seen in crypto and equities in last several months.

Now the situation into the end of 2022 and 2023/24 cycle looks completely the inverse of that (2021) but with still some potential same characteristics (stay at home if new pandemic). Let's outline why that might be, and is not just my assumption, there are facts within the broad financial sector and economic (inflation) side that explain the tightening in front of us and broad impact on the markets: -Tightening policies from central banks around the globe, led by the FED, and reduction of easy money and credit within the system within upcoming years, for central banks to fight inflation is going to lead to capital leaving high risk areas (and already has to some extent)

-Higher costs of a mortgage, lower credit consumption, and lower spending, all of which is likely to pull easy money away from markets, much of which companies need to create opportunities of high money earnings/revenue conditions, which typically create larger moves in markets (as we have seen in late 2020). If such inverse conditions are present for the next few years, which is a likely scenario, the pull of the easy money out of the system is likely going to shrink the opportunities and the upsides in many markets.

-More layoffs due to recession in next two years will lead people to pull money away from markets and use it as a source of a cash cushion, typically its what happens in such conditions, and why so many are forced to sell their investments at the market lows often when markets crash and stay down for a while, due to cash balance shrinking and requiring that extra influx, which might come from what the trading balance with their broker might be, whether its a trader or investor. Again this might not be a systematic problem if the crisis is short and is all gone within a year. If prolonged for a few years it becomes a significant contributor and obvious, which I believe the current inflationary crisis is very likely to be (more about that in other articles). To put it shortly, money gets tight, brokerage accounts get depleted as the cash reserves are needed.

-Fewer IPOs, fewer small-caps movers (2008 provides some examples, but it's limited because it's not an inflationary crisis, and 1970s markets were not developed enough yet on smallcap or crypto or innovation side to use them as a good comparison).

A generally tighter monetary environment with higher inflation leads to less innovative companies entering into markets because investors do not like to take excessive risks where they know such riskier companies will have trouble accessing higher interest rates of credit lines, or just the equity from the market due to shrinking liquidity. All of which means less smallcap participation, the question is obviously, how much? 5%? 15%? Less IPOs, less SPACs, less pumps. But not necessarily in very big plunge of total numbers, but still large enough to be noticeable most likely.

Summary of the above would be: Trading and investing is already difficult enough when the economy is functioning well and low-interest rates with plenty of QE are at disposal.

It is more difficult for the majority of traders and investors (especially investors) to extract an edge in bear markets or higher inflationary markets when monetary conditions tighten up and the economy enters recession. This is a fact.

Potential decrease in liquidity and number of opportunities (small cap equities especially)

It is no surprise if one checks the small-cap equities and the number of gappers / moving tickers on the day, there is a clear connection to the extremes tied directly to macro markets "health" and tightness of monetary policies from central banks.

Let me explain this a bit further. Overall on average, small caps trade within their realm which is not too connected to broad macro markets, there is always something moving in small-caps. However, there is a noticeable increase or decrease of activity in the extremes of it, which are usually macro-related and driven.

Easing and growing economic conditions (more opportunities):

This means, that when the central banks step into easing policies (QE, lowering interest rates) all of sudden, and there is an upwards turn in the economy, it will typically lead to higher increase rates of small-cap movers, and an increase in the ranges, typically leading to stronger cycles in small-caps.

Tightening and worsening economic conditions:(less opportunities):

At the same time, there is an inverse, when central banks start to tighten and broad economic conditions start to worsen, and large-cap equities begin to struggle, it will lead to a decrease in the total activity of movers in small capers.

If we extrapolate from that, likely, an inflationary environment, combined with tightening monetary policies across the globe will lead to capital being pulled away from riskier markets to an extent, increasing the chances that small-caps might struggle more rather than flourish. This could be the case for some other markets as well, such as real estate, or large-cap equities.

The patience threshold

If a number of opportunities in the market decrease along with "easy pump" money gone, think of how this affects you and your edge. Every trader or investor has a time window under which he/she starts to become impatient and says "this is too much" when the market just becomes too dry for too long. Especially traders only specializing in one particular edge with setups that are more rarely present will eventually at least once in 3 years land into such a major testing area, where one of their markets will just go into dream-shattering mode. And by dream shattering I mean, where trader for the first time realizes that this edge or trading, in general, might not be long-term sustainable because without market delivering more opportunities than it currently is, there is no way to make consistency out of this process.

The patience threshold is tightly correlated with the size of your playbook and the number of markets you invest in or trade-in. The smaller the number of setups and markets exposed to the tighter that patience window will be (the sooner you might get into trouble).

To explain this further, let's use smallcap equities of the US as an example. From personal observations typical trader will have 1 month of "acceptable patience" time frame, whereas if the market is very dry on delivering opportunities on that edge trader is using, it is still considered acceptable. It's acceptable for the market to go 1 month into the dry mode, because of how many samples of trades a typical smallcap trader will have over 3 months.

However 2 months is when the patience starts to become unacceptable, and especially beginners who go for the first time through such a drought will sometimes start looking into new strategies and edges or just quit trading and investing because the length of the market dry period is just too much to take. The insecurity of the future is too much to handle because one just doesn't know if those very long dry periods might come in bulk in near future.

The reason why the above matters, is because it's highly tied into playbook size. The less of setups and edges one has, the more you are exposed if potentially market participation and activity all of sudden starts to decrease by a large factor, typically as what happens within financial crisis, recession, or perhaps some sort of regulatory implementation.

And its not just the playbook size that matters, or the quality of edge, but the number of markets one is exposed to. The fewer markets (especially un-correlated niche markets) the more likely it is to land into a prolonged dry period. The more markets one is exposed to, the more likely it is that some opportunity is in play somewhere. However, that obviously comes at expense of the increased difficulty of actually developing edges across few rather than just one market, which is another topic in itself.

Therefore to expand patience window = playbook size increase + more markets.

One might be wondering, if this is a serious issue, and there are many practical examples of how one can see this being issue, then how is this point not raised more often? (especially if we highlight the last 10 years of modern retail trading). Why aren't more talking about how important it is to have a playbook stacked, and not be exposed to just a single market?

The answer to why this is not addressed much, is especially over the past 10 years retail markets were just under constant upwards growth as broad economic conditions over the past 20 years were mostly within easing conditions with few recessions here and there, but none were long lasting or highly inflationary. Therefore we are entering this situation only for the first time since modern retail trading, at least on a global basis that is.

To explain this more, it is within the frequency of prolonged economic crises and the average quitting rate of market participants. In other words, a large portion of market participants will drop out within a few or several years, or decrease their activity a lot (even in non-recessionary economic conditions), meanwhile prolonged inflationary crises (such as the 1970s one) only come about once in everyone's lifetime, especially if we are talking about the global inflationary crisis such as current one, and not more frequent-regional ones (limited to single country).

The combination of those two-time factors explains why most don't worry about it, because you only have to worry about it once, but once that "once" really comes into play, it can be prolonged for so much (a few years) that all of sudden your entire edges and investing approaches come under major stress testing phase. They are likely to fail unless you have ensured a wide enough playbook, with few different market exposures, and especially both long and short edges.

Therefore ensuring that if pie chunks shrink down, you have to find out how to make it through by just getting crumbs, but finding crumbs in many more places rather than just seeking that one place where a full piece of the pie usually hangs out. Which is where playbook size and number of market exposure, plus both long and short edges come into play.

This reference is rarely mentioned within trading material because a lot of trading material is shared by those who haven't even been in one particular market for more than 5 years. It typically takes 5-10 years participation of within a single market to experience going through major crises and liquidity/opportunity shrinking down. Much of the trading material is shared by beginners in the first place, and even if experienced traders share material it's often seen that they flop from one market to another, never spending more than 2 years within a single market, which decreases the chances for them to absorb just how key the reference and point made above is. This should help to explain a bit why this point is rather very important if tough economic conditions lead to shrinking market participation and opportunities and how this increases the chances of one to give up if playbook size is not expanded beforehand.

Tight patience window increases the chances of making mistakes

If the number of opportunities decreases and inflation keeps all bullish opportunities smaller (caps them on upside) it creates the combination of decreased opportunity with decreased payout, increasing the pressures on patience and discipline (even for bearish edges). All of which leads to a higher chance of creating mistakes. The only very practical thing to implement and combat this is expanding the playbook, research new edges, and increase participation across more markets than just one, so that there is always some opportunity somewhere, especially if one particular market dries out much more than the rest.

Traders who do not address the point above are highly likely to hit the period of constant complains, and eventually might even quit, if they haven't put work into addressing the point above, to prepare for that one period where the number of setups on average might decrease quite a lot.

Therefore expanding the playbook might be more important than ever.

The "FED bluff" as reason for not doing anything about it

Some might argue: "But surely the FED will inverse its rate cutting policies, and all will be well again, because recession will force them to do so."

To think that current recession conditions are all somehow FED rate-tightening related would be a huge oversimplification. Strangely those stories do circulate. While Fed's easy monetary policies surely did help to create a need to implement an inverse (due to over-reaction), it doesn't explain all the supply chain-sided issues that from many more angles are pressuring global inflation and have nothing to do directly with FEDs or any other central bank monetary policy.

If the economy hits into deeper recession some argue that rate-cutting policy will follow (2023), along with QE. I wouldn't be so quick to believe that. Mostly because inflation will persist for quite a long time, based on all the noncentral bank factors, which will not leave much ability for central banks to implement major rate cutting policies. While slowing of the rate hikes could happen, cutting all the way back into ease like the territory of 0 rates is unlikely.

This means that this goes into the whole point of this article, the tight monetary policy combined with inflation will remain present most likely and therefore impact the markets as outlined above. Many perma bulls are using wishful thinking in hoping the FED might inverse the rate hiking policies, especially since history does not suggest that as too highly probable scenario (if inflation does not come down quickly). However it is true that inflation is major component to validate that story, and it most likely wont be straight path to 5%, if FED and some other central banks were to meet that.

If using the 1970s inflationary crisis as a reference point, we can conclude that living standards might stagnate or decrease over next few years, revenues decrease for many businesses and some businesses might experience layoffs.

If a similar situation occurs (which I highly believe it will to perhaps an even larger extent), then ask yourself how many participants are still willing to stay within markets if it happens. And that doesn't just include day traders. Even long-term investors might be more willing to pull money out of equity investments just for sake of having cash on hand, which can create a decrease in retail flows and overall market activity. Since the US has always been credit driven society over the past few decades if inflation and interest rates were to go quite a lot higher, there could be a very notable effect in terms of how cash needed would impact the decisions of market participants, in terms of possibly triggering withdrawals to some extent.

First long-term macro environment of toughness in recent history

Future expectations are very important in terms of keeping participants to stay within the game of markets. If economic projections are good if there are no layoffs on the major scale seen within the economy, if opportunities for business revenues are growing as within a normal economic situation, then people do not worry.

Many who come to markets instantly start to build their expectations on what it is to expect making out of trading/investing within X months, X years.

But what is not often mentioned, is for many who make such calculations, they come from an environment where their income (outside of markets) is already quite stable, or on the increase, so they enter the very difficult game of markets with high expectations because there is no pressure from whatever sustains them trough initial years of their career in markets.

Now that was the norm forever in markets or at least digitalized retail markets, which were born in 2000 when the internet showed up.

Since then we only really had two crises in between (the 2000 dot com bust, and the 2008 banking bust) but none of that were very inflationary crises, and none lasted for a long time in its primal magnitude. The people inflected by them also were very asymmetrically distributed, some were hit by crisis a lot, some very little, and some almost none.

It is a completely different story when we talk about a global inflationary crisis such as one currently in progress, as no one is hidden from it. Inflation gets eventually to everyone. And while yes, not everyone is proportionally impacted due to differences in incomes and exposure, it still leaves a much larger impact on all participants, unlike the prior 2000 and 2008 crises. Obviously, if you are reading this article in 2022 keep in mind, that my projections are meant for 2023, 24, 25 assuming the inflation remains elevated, and the real reflection of what is said in the article becomes more and more noticeable as the years go by. They are not yet visible as of writing this article. Inflationary pressures take time to put the shackles on economic activity and to be reflected in market participation and liquidity. So the summary of the point above is: For the majority of millennials or slightly older generations who have started to participate in markets in the past 20 years, the references of the past don't provide a good clue on what should happen to market activity or participation rates in the current crisis, because this one is different than the past two crises present in modern markets. This one will have more connectivity to the 1970s and since modern highly liquid markets were not yet present at the time there is a drawback to using past data to create good projections, especially when it comes to fallout of daytraders or smaller markets activity rates (none of which were common back then at least not in highly engaging rates).

The other side of the argument made above:

Some room for a counterargument (2021 reference) and why it might not matter

If working conditions or earnings conditions of companies and consumers toughen it might lead more people to the markets, there is some argument to make about that from 2021 after the second wave of lockdowns. As conditions tighten and become harsher, some do rush to market as potential easy-to-extract money opportunity, when opportunities elsewhere in the physical economy might be shrinking (due to lockdowns). There might be some truth to that, but keep in mind this is all very much short-sighted, which is why the argument might fall this time in 2023. So even if there is a rush all of sudden in upcoming years to market from some sort of new QE implementation, it is unlikely this would be sustained in terms of delivering a participation increase over the long run if we take into account that negative pressures of inflation and worsening of living standards on the counterweight of that.

The content of the article is especially true for non-US market participants as inflationary pressures are likely to be much higher in the majority of other countries around the globe. For those engaging in trading US markets while not being a resident of the US, it is likely the above-written article applies more to you, than it does to someone from within the US. This is just due to the difference in the resiliency of the US economy against inflation versus many other countries. However it does not exclude by any means US residents away from it, since inflation has increased already within the US just as much, and the FED is likely to impact markets on US internal side a lot if they keep the tight policies implemented or increased at the pace into upcoming years.

The big picture (it's not the apocalypse by the way)

Since the tilt is quite depressive in the article, let me restate it within my rough expectations of what it might be more precisely, in terms of a decrease in participation and liquidity.

We might get 30% of total market participants dropping in the next years, with liquidity as well dropping to that extent (vs 2022 flows as a comparison). The total amount of "tickers/assets in play" might also shrink by a third in total.

If you trade non-US markets, chances are that shrinkage of participation and liquidity decrease will be significantly higher than in US markets. This is one of the good reasons why US markets might pull some of that external activity and bring them into US markets (to replenish the dropout to an extent).

If you were to believe that inflation across the emerging markets would increase quite a lot more than within the US, and the average participant is less capitalized in less wealthy countries, it shouldn't come as a surprise that those markets might see a larger overall decrease, especially small cap markets in equities or currencies of such economies.

This is one of the reasons why if one is thinking of picking new markets of interest or research and learning for upcoming years, it is highly likely that the US is your best bet to either stay in or start learning about. The resistance of that market to keep still somewhat decent liquidity is higher than within most other places. If you are investor or trader in non-US markets only and that's where your edges are primarily, now might be a good time to find secondary routes into US markets as well.

But a 30% overall cut on liquidity and participants is quite significant. Especially to those who entered into full-time day trading in 2021 and built their entire future expectations on profits and opportunities based on the markets of 2020 and 2021, we could also quickly come to agree that it is plenty of individuals. Obviously that 30% is a rough estimate by my side, and could turn out to be higher or much lower, or to even be completely wrong if everyone suddenly starts to find markets as their last resort of quick income amidst economically tougher conditions. As always I try to keep my mind open when it comes to any macro views, and while there is a possibility for that to happen, the history of how the market participation in financial crises and inflationary environments goes the data doesn't point out to be likely for where we see more participants in next year. Instead, it points out more towards the inverse of that, and so does the basic economic logic.

Overall we would likely see those more capitalized to stay within the game regardless and those with robust edges across multiple markets, or if within just a single market a must probably to have both long and short edges. If liquidity and market participation drop this will be a no-brainer example of where traders with both long and short edges will have more opportunities and fewer reasons to complain about, than those who are only trained on one side of the trade. Keep this in mind if you have been thinking about exploring that other "dark" side of the positioning, this might just be the right time to do it.

Just as the economy will be taken through a major testing phase in upcoming years as revenues will shrink in some sectors, earnings will shrink and the expenses will increase, so will the trader's edges will be taken under test.

The fewer patterns and the weaker the overall edge you might have, the higher the chance of landing in a difficult spot in upcoming years, taking into account that what was said in the article above turns out true in terms of liquidity and participation dropout rates. And while that might seem like an encouraging final message, it might not be so.

Trading and investing are already difficult on their own, any extra pressures of edge refining/exploring within a short amount of time just increases the difficulty. It makes the difficult process of creating sustainable and consistent progress more likely chaotic and un-consistent. Either way, the challenge is likely to increase, unless the central banks across the globe bless everyone with a bunch of new massive QEs in upcoming years on monthly basis.

Rough outlook:

-equity and crypto markets might struggle for a while to create any sustainable uptrends. Bullish edges are more likely to fail or get into trouble. However since both markets were already pulled down quite a lot, the downside might also not be that great, it's possible to see both markets stagnate, forcing traders and investors into deploying both long and short edges.

-currencies and risk-off assets are more likely to trade within strong directional trends because certain economies will have large structural issues in upcoming crises, which makes those currencies exposed versus the USD. Therefore understanding the macro trend of the currency is a key part of selecting the right long or short-sided edge.

Conclusion

The idea behind this article is not to spook or provide depressive content. It is to straighten anyone whether beginner or experienced into anticipating a more challenging environment and taking a serious look into expanding playbook and potential as a market participant right now so that enough opportunities can be extracted within a potential market environment where opportunities by default shrink in their number.

If you are a long-biased participant and ever thought about exploring the edges on the short side this is perhaps the right time to do it, more than any time before.

One might ask why the short side primarily? Well because in challenging economic situations rallies if they do happen are more likely to be sold off strongly. It is just the nature of long-term decay that becomes stronger to the downside rather than sustained upside when the challenge is on, especially for a market that just a year ago priced every single stock in the large cap index into super high valuation territories. And that includes the small caps and even currencies to some extent. The idea is not to expect no rallies, or everything to be selling off all the time, it is rather to expect rallies to fail a bit quicker, and downside pressures to be overall at a higher pace.

But do not lock everything said within just "short edge" expansion necessity, that is not the message here. It is to think about it holistically in terms of how to address the edges regardless of what they are, and expand into more markets if needed, to take as much control over the trading process within an environment that might provide fewer opportunities overall.

And yes, this is easier said than done, it's a large task if one was to take it seriously. The idea of this article is not to discourage anyone to keep trading or a beginner to not entering the markets, it is rather to highlight the increase of difficulty likely from the upcoming global economic situation. It is always better to prepare for the challenge even if the challenge doesn't end up being that difficult or deep.

Comments